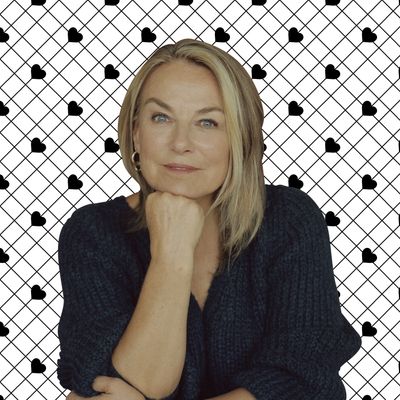

When I first met Esther Perel — some four years and four boyfriends ago — we took a walk and a subway ride without being noticed. These days, it’s difficult to cross a city street with the go-to relationship expert and psychotherapist without people doing a double take. It happened to us several times in the crowded Soho restaurant where we met last week. Amid the noise, and some rubbernecking neighbors, I tried to pin Perel down on the questions that have been haunting me of late. Is marriage still something to aspire to? How do I know when a partner is the right person to do life with? And moreover, why do so few people — in any romantic configuration — seem fulfilled?

I figured if anyone was going to have the answers to these Big Questions, it would be Perel. Her books Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence and The State of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity have, as their titles suggest, invited us to redefine conventional notions of marriage and relationships. She’s a famous couples therapist who has reportedly (she did not confirm) counseled the likes of Armie Hammer and Elizabeth Chambers. She’s even developed a card game. And one engineer with a broken heart has made Esther into an unauthorized bot.

I understand why. Spending time with Esther is nourishing. It’s also amusing — in part because she is unable to suppress her own curiosity. During a video call in the pandemic, she kept peering into my Zoom background, trying to figure out who the man in the background was. At our dinner, she plied me with questions about my dating life: Do I offer to pay on a first date? And what happened to the last boyfriend — the one she met? At some point, she let me dive in.

So many people I know are unhappy — or, at least, they express a void. Married parents feel like they’re failing at their work or at home, single people struggle to find partners that stick, divorced parents sometimes seem the happiest of the lot but have their own gripes. The grass is always greener, but it seems as if the grass is not green anywhere these days. Why is there so much disappointment in modern relationships?

I think they’re unhappy because their relationships don’t ignite them the way they would want or the way they had imagined. It doesn’t meet the myth of their romantic aspirations. And they’re unhappy because they find themselves dating, dating, dating, looking for something, and constantly saying, “I haven’t found the right person yet.” “I didn’t get dazzled.” “I didn’t experience a chemical reaction in my belly.”

There’s also more permission to speak about it now. This is the first time, I think, in the history of humankind that the survival of the family depends on the happiness of the couple. And this is particular to the west, where we live with a nuclear model of family that is highly complicated, very isolating, and depleting to the couple.

I believe even more today this notion that you can’t ask one person to give you everything. But it’s not just that — it’s that you absolutely need diversification of relationships. You need friends to bitch about your partner with.

People in intimate relationships are often isolated. They see fewer people, they do fewer things. And there are many people who have a better life when they’re not in an intimate relationship because they have a very wide social life. So we have to stop thinking that if you don’t have a romantic relationship, you’re incomplete.

You’ve written about how, historically, marriage was an economic arrangement between families. And now it’s an identity project — two individuals seeking self-actualization. Has that made our relationships less transactional? More?

In a way, more. We are doing romantic consumerism. I’m shopping for something, and I have a list of what it needs to be. On the one hand, we want to ask more, which is not a bad thing … but we want to pay less. And just as emotional language has entered the business world — where we talk about psychological safety and vulnerability — business language has seeped into romantic relationships. We want “return on investment” and to “hedge our bets” and “this is not a deal I signed up for.”

And the economy for dating, for many people, exists almost exclusively online. Friends don’t think to set you up because there’s an app for that. IRL, single people may have blinders on or be afraid to approach one another.

In the past, you met people on planes, in bars, in a line to a museum, you name it. And now if you try to talk to people around you, you’re weird. Someone says, “Can I buy you a drink?” and you think they’re creepy. Technology now mediates our relationships. And we have developed a major sense of social atrophy.

Look, you don’t come to dating with a history of dating. You come to dating with an entire history of socialization. So if I am embedded in my phone and disregard the world around me, then when I get out of the cab, I forget to say hello, good-bye. Then I enter a building and somebody opens the door for me and I don’t say thank you to that person either, and then I’m in the elevator and I’m in fact talking to somebody on my phone. So how do you interact with the world around you? How do you notice people?

There is a firehose of options being spat at you with these apps. So many swipes and choices —

But choice is not the same as freedom. Freedom is actually the ability to make a choice in the middle of restrictions.

Ooh — that’s good. I’m going to write that down.

I understand the promiscuity of choice, but I also understand that there’s something very ironic about trying to find a soulmate on an app. First of all, the fact that it’s even called a soulmate is in and of itself really fascinating because the soulmate used to be God. And now we are really looking in the realm of relationships for what people used to look for in the realm of the divine: transcendence and mystery and wholeness and meaning.

You’ve written a lot about this idea — that we have unrealistic expectations for our partner.

I still think that, and I think that the expectations are only rising.

Why?

Because I think the world has become even more uncertain. In the west, we have less religion, less trust in government — fewer communal hierarchies and structures to guide us. So everything is on us and our partners. You decide if you want to have children, if you want to have sex, who’s going to wake up to feed the baby, whose career matters more, whose family we’ll visit for the holiday. All these things were once clearly laid out. Now all of these are negotiations.

One thing you’ve noted is the rise in relational ambivalence, “too good to leave, too bad to stay.” Explain the term.

In Freudian language, ambivalence is the ability to hold contradictory feelings toward a person. A child loves their mother, but can also sometimes be extremely angry at her. A person holds love and hate, attraction and disgust, excitement and boredom, connection and disconnection with a person. The ability to be able to hold these contradictions is often seen as a sign of maturity. What has happened now, especially at the end of the pandemic, is that many people arrived at a more polarized notion of ambivalence: a relationship is too good to leave, too bad to stay. What shall I do? As if there’s only two choices.

I know exactly what you’re describing, and I find it a paralyzing feeling.

It’s only paralyzing when you want to answer it, when you feel like you need to make a choice.

But at a certain time and place, if you’re confronted with this idea of committing to someone, how do you make that choice?

Look, I always make the distinction between love stories and life stories. There’s many more people you can love than people you can have a life with. There are a lot of people you can meet on a beautiful trip — you come from different worlds, but you have a moment of connection in a particular place. Beautiful, but those are love stories. Just don’t try to turn every love story into a life story.

Which love story should you turn into a life story?

The ones that look like they could be a life story, like where you have shared values, shared aspirations, shared visions for the kind of life you would like to lead.

The question I would ask myself is, “Is this a person with whom I can imagine the journey of life?” That involves economic issues, family ties, social life, professional aspirations to different stages of life. It doesn’t mean that you’re married for life, it just means: Can I project it?

One question I ask all my patients is, “If you were to break up and you had kids, can you imagine this?” or “Do you think you are with somebody vindictive?” because you know if a person has grudges. Listen to what people tell you, and do not think that you are so special that with you, they won’t do the same.

But many relationships, in the end, you choose when the grief of what you would lose is too big to bear. Grief is directly related to choice. There is no choice without loss, right?

True. We always hear that marriage is a choice. Commitment is a choice. Is it?

Yes. But I would say in the past, our social lives were primarily dictated by rules, duty, obligation, and commitment. And in the other parts of the world, it still is. That is how social living is organized. You don’t go to see your grandparents because you feel like it. You go because you have to, because it’s what you do. We have replaced commitments with feeling, and we have made commitments depending on feelings and choices. That is a major shift.

And one of the essential denominators of those feelings is authenticity. And authentic feelings are something that is hard to come by, because now I need to know: Are they really true? How authentic is this? Do I love you? Do I love you enough? It is a job to find out what I truly feel.

But when I say there’s a distinction between a love story and a life story, I mean that sometimes the relationship is your source of intimacy, of closeness. Yet sometimes the relationship is infrastructure. It’s scaffolding. And that is also a valid reason, because it becomes the beachhead from which you get to pursue other things. It gives us both social status. It gives us access to community, invitations to dinners. It gives me a sense of belonging. I have my family, I have my children, we come together as a unit.

I think that we have to make the word choice a little broader than just “how great is my marriage?” Instead ask: “What does my relationship enable me? Is it generative?” And sometimes the relationship is oppressive, but the family structure is generative.

Not everything is a designer production. There’s this notion that you control everything, you hack yourself, you plan your longevity. We are surrounded with strategies of control. But sometimes there is a pragmatism that accompanies marriage. It’s really not popular these days. I get it. We live twice as long, and the marriages last longer.

For someone who is famous for creating permission around relationships, you sound to me a little nostalgic for something more traditional. Is that the case?

[Laughs.] No. I think when you have commitments and duty, you do what you need to do. You often choke. But at least you get clarity and you know that your happiness comes from having done what you were supposed to do. Today, your happiness comes from knowing that you’ve lived true to yourself. Well, that is a much more complicated thing to do or to know.

I’ve never advocated for anything … except for plurality. There cannot be a one-size-fits-all for something as complex as modern relationships. Marriage is a story. Relationships are stories. They have characters, roles, protagonists, auxiliaries, beginnings, middle, ends. They have chapters.

Sequels?

Sequels. Yes.

And the story … I always invite people to write often, and to edit well.

The stories are things you can change. You can decide to stop it. You can start a completely new story. Or you can rewrite a different ending to the story. That story gives you a lot of agency. Not control — agency. And agency comes with freedom.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.